Indian Mother Of Seven Breaks Caste Barriers

Married at 14, the mother of seven, Kakuben Lalabhai Parmar was well into adulthood before she came face-to-face with a man who was not a close relative.

Married at 14, the mother of seven, Kakuben Lalabhai Parmar was well into adulthood before she came face-to-face with a man who was not a close relative.

In the cattle-herding community to which Parmar belongs, one among a cluster of groups categorized by the Indian constitution as “scheduled castes,” women were traditionally bound not just to their region or village but to the home.

“My group was treated as untouchables,” said Ms. Parmar, 50. And if the community was untouchable, its female members were still more disadvantaged by being invisible.

Miraclulously, Parmar’s life was transformed roughly 20 years ago by a not-for-profit organization called Sewa .

“I already experienced the biggest change in my life,” she says, “when I first got the chance to come out of my house and participate in society.”

That was roughly 20 years ago when the not-for-profit Sewa Project formed a unit in her village to help preserve endangered handicrafts and, equally, to provide the people who make them a form of alternative employment.

“We never even thought of getting income from selling this stuff before,” said Ms. Parmar, who sews patchwork embroideries that incorporate vivid threads and reflective shards laboriously cut by hand from mirror scrap she buys by the pound.

The cloth, at least, may be familiar to some, since it is the kind used in the making of a slouchy “It” bag being hauled around this summer by Cameron Diaz , Nicole Richie and other celebrity entities.

The price tag on a satchel made from mirrored patchwork and bearing the label Simone Camille is about $2,000, a sum equivalent to two years of Parmar’s income.

Yet even on the modest $60 a month she earns sewing pillow covers that require almost a week’s work and that sell in her local market for $15 a pair, she has become the family’s chief breadwinner. She holds title to her own cattle, has a personal account with a microfinance credit union and is quick to point out that while this may seem insignificant compared to such symbols of Western wealth as reliable electricity and plumbing, it is considered a vast change in circumstance for a woman from rural India, even now.

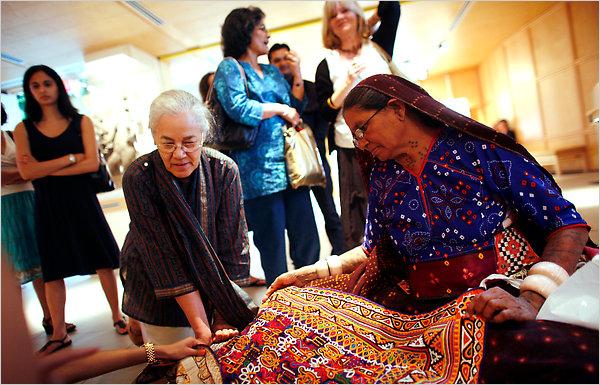

“When I was a girl, all the assets belonged to the father or the husband or the brother,” Parmar says. Squatting on the floor of the Asia Society’s grand marble lobby, she demonstrated her technique for cutting mirror shards into diamond, oval and triangular shapes and a pointed form called a “crow,” using the sharpened edge of a terra cotta roof tile. She multitasked ceaselessly, stopping to spread out pillow covers for one buyer’s approval, and explain the eye-dazzling motifs she uses to another, all the while keeping a sharp eye on the sales totals, eyeglasses perched at the tip of her nose.

“In those days, the husband was in charge of everything,” she explained to a visitor. “What could you do, with no skills and no education?”

Now as a globetrotter, an informal ambassador for Sewa and the Crafts Council of India — one of a growing number of groups committed to preserving traditional folkways in India, a country where, by some estimates, 40 million to 60 million people gain at least part of their living making handicrafts — she finds herself in circumstances she could never have foreseen.

Click here to read the full story:

By Guy Trebay

New York Times

Photo Credit:

Kirsten Luce

Related links:

More About India on AWR